Dersu Uzala: The Hunter

Full of challenges and dangerous adventures the meaning of this story goes far beyond the plot, it's a story about the brotherhood of people and that we are all children of the same land.

This Natural Intelligence episode on the Wildcraft Forest Channel presents a classic Russian biographical drama about an indigenous hunter with extraordinary personal qualities on a journey through the taiga-forest. Dersu Uzala: The Hunter is available at the Wildcraft Forest Channel on Roku and YouTube.

Peter Farb who wrote “Man’s Rise to Civilization” in 1969 said:

"No sooner did the first Whites arrive in North America than a disproportionate number of them showed that they preferred Indian society to their own.

Throughout American history, thousands of Whites exchanged breeches for breechcloths.

Why did transculturalization seem to operate only in one direction?

Whites who had lived for a time with Indians almost never wanted to leave. But almost none of the "civilized" Indians who had been given the opportunity to savor White society chose to become a part of it.

Nor does this problem relate solely to the American Indian. Some of the first missionaries sent to the South Seas from London, in the eighteenth century, threw away their collars and married native women”.

Dersu Uzala: The Hunter is a 1975 Soviet-Japanese biographical adventure drama film directed and co-written by Akira Kurosawa. The film is based on the 1923 memoir: Dersu Uzala by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev.

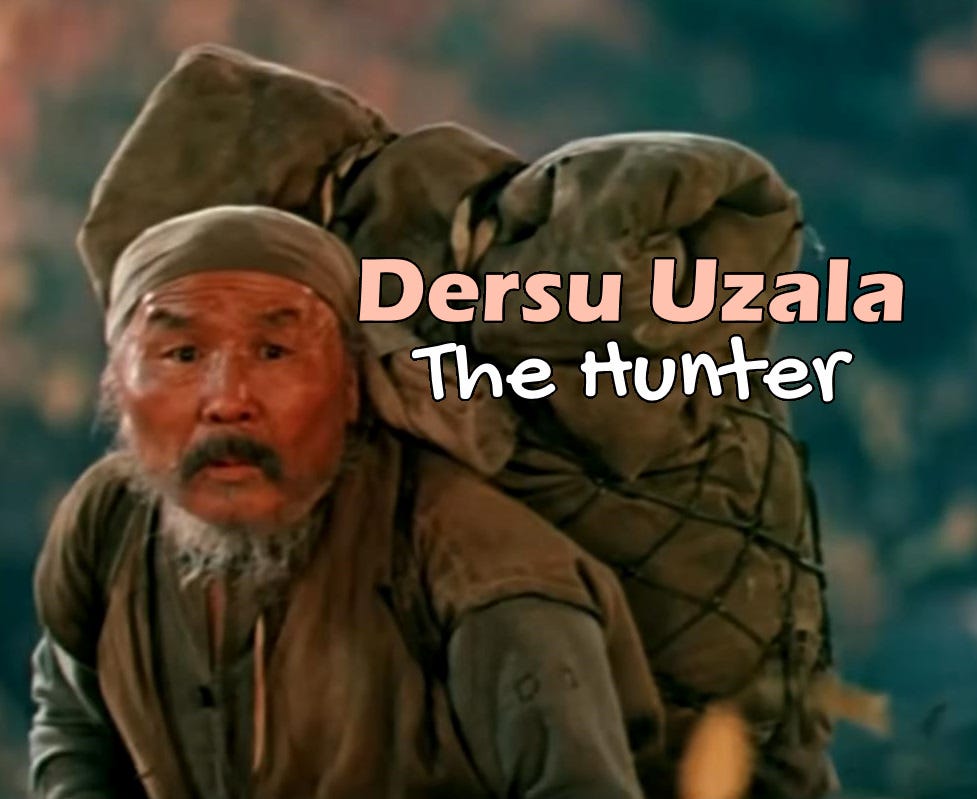

The story is about Arsenyev’s exploration of the Sikhote-Alin region of the Russian Far East over the course of multiple expeditions in the early 20th century and his chance encounter with an indigenous trapper and hunter Dersu Uzala. Uzala lived from 1849 to 1908 and was from the remote Okhotsk–Manchurian taiga.

Uzala would become Arsenyev’s guide and their friendship would form as Uzala demonstrated extraordinary personal qualities. Their journey through the taiga-forest, full of dangerous adventures, is the plot of the film, but the meaning of the story goes far beyond the plot: it's a story about the brotherhood of people and that we are all children of the same land.

Together the two men would experience a clash between their two cultures which were defined by two very different world views.

This spectacular film is shot almost entirely outdoors in the Russian Far East wilderness which in 1975 was still very remote and for the most part held the same pristine landscape as when Arsenyev explored the region decade before.

The film explores the theme of a native of the forests who is fully integrated into his environment, leading a style of life that will inevitably be destroyed by the advance of civilization. It is also about the growth of respect and deep friendship between two men of profoundly different backgrounds, and about the difficulty of coping with the loss of capability that comes with old age.

This film provides certain lessons about the elements of first contact between cultures and how humans who lived directly in this landscape for thousands of years simply faded away into history largely without being noticed.

Dersu Uzala: The Hunter won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, the Golden Prize and the Prix at the 9th Moscow International Film Festival, and other awards. It was also a box office hit, selling more than 21 million tickets in the Soviet Union and Europe in addition to grossing $1.2 million in the United States and Canada.

Directed by Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa and staring Yuri Solomin as Arsenyev and Maksim Munzuk as Dersu Uzala, the film was Kurosawa's first shot in 70mm. The film's success helped revitalize Kurosawa's career, leading to the production of other films such as Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985).

It’s important to place Dersu Uzala into context. Released in 1975, during the height of the Cold War — a period marked by deep divisions and global tension — ‘Dersu Uzala’ emerged as a collaborative effort between Japan and Soviet Russia. It’s at odds with an era where international cooperation was at an all-time low.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Communist Party elite rapidly gained wealth and power while millions of average Soviet citizens faced starvation. The Soviet Union's push to industrialize at any cost resulted in frequent shortages of food and consumer goods. Bread lines were common throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the period is often described as the Era of Stagnation. In the 1970s, the Soviet Union and the United States both took a stance of "detente".

The movie for its Soviet audience may have brought about a cultural pondering about periods of transition, where the old ways transition to the new, and leaving one with an inevitable sense of loss for the past.

This sense of loss or at least a pondering can be found within all of humanity and it is timeless which makes Dersu Uzala valid for the ages.

We hope you that you enjoy this presentation.

Within this presentation we have also included additional commentaries and presentations that support the role of spiritual stewardship.

The Dersu Uzala: The Hunter can be found on the Wildcraft Forest Channel - on Roku and YouTube.

Visit the Wildcraft Forest Channel Program Guide: www.wildcraftforestchannel.com

Explore our learning and certification programs that connect people with nature: www.wildcraftforest.com

Sidebar: The Shamanic Nanai People of Russia

The Nanai believe that each person has both a soul and a spirit. On death, the soul and spirit will go different ways. When a person dies their soul lives on, as the body is merely an outer shell for the soul.

In the film Dersu Uzala: The Hunter, Dersu refers to himself as being from the Gold People, which represented a common Russian name for the Nanai People who may have been part of the ancestral group which crossed the land bridge into North America thousands of years ago.

The Nanai people are an indigenous group of Tungusic people found in East Asia who have traditionally lived along Heilongjiang (Amur), Songhuajiang (Sunggari) and Wusuli River (Ussuri) on the Middle Amur Basin which straddles boundaries of Russia, China and Mongolia. The ancestors of the Nanai were the Wild Jurchens of northernmost Manchuria, which is now the region of Outer Manchuria in Russia's Far Eastern Federal District.

A photo taken in 1906 of Dersu Uzala, a Goldi hunter, and guide to Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev on multiple topographic expeditions in the early 20th century.

A common self name for the Nanai are the Qilang which means 'those who live by the river'. There primary survival was linked to fishing, hunting and trapping within estuary forests.

The Nanai are mainly Shamanist, with a great reverence for the bear (Doonta) and the tiger (Amba).

They consider that the shamans have the power to expel bad spirits by means of prayers to the gods. During the centuries they have been worshippers of the spirits of the sun, the moon, the mountains, the water and the trees. According to their beliefs, the land was once flat until great serpents gouged out the river valleys. They consider that all the things of the universe possess their own spirit and that these spirits wander independently throughout the world. In the Nanai religion, inanimate objects were often personified. Fire, for example, was personified as an elderly woman whom the Nanai referred to as Fadzya Mama. Young children were not allowed to run up to the fire, since they might startle Fadzya Mama, and men always were courteous in the presence of a fire.

The deceased were normally buried in the ground with the exception of children who died prior to the first birthday; these are buried in tree branches as a "wind burial". When a person dies their soul lives on, as the body is merely an outer shell for the soul. This concept of a continuing soul was not introduced to the Nanai by Christianity, but is original to them.

The Nanai believe that each person has both a soul and a spirit. On death, the soul and spirit will go different ways. A person’s spirit becomes malevolent and can begin to harm their living relatives. With time, these amban may be tamed and can later be honoured and respected; otherwise, a special ritual must be performed to chase the evil spirit away.

After death, a person's soul is put into a temporary shelter made of cloth, called a lachako. The souls of the deceased will remain in the lachako for seven days before being moved to a wooden sort of doll called a panyo, where it will remain until the final funerary ritual.

The panyo is taken care of as if it is a living person; for example, it is given a bed to sleep in each night, with a pillow and blanket to match its miniature size. The closest family member is in charge of taking care of the deceased’s panyo. Each night this family member puts the panyo to bed and then wakes it in the morning. The panyo has a small hole carved where the mouth of a person would be, so that a pipe may occasionally be placed there and allow the deceased to smoke. If the family member travels they will bring the panyo with them.

The dead’s final funerary ritual is called kasa tavori and lasts three days, during which there is much feasting and the souls of the deceased are prepared for their journey to the underworld. The most important part of the kasa tavori is held on the third day. On this day, the dead’s souls are moved from the panyo into large human-looking wooden figures made to be about the size of the deceased, called mugdeh. These mugdeh are moved into a dog sled that will be used to transport them to the underworld, Buni. Before leaving for Buni, the shaman communicates any last wills of the deceased to the gathered family. For example, in the anthropologist Gaer’s account of this ritual, one soul asked his family to repay a debt to a neighbor that the deceased was never able to repay.

After this ceremony, the shaman leads the dog sleds on the dangerous journey to Buni, from where she must leave before sunset or else she will die.

After kasa tavori, it has previously been practiced that the living relatives could no longer visit the graves of the deceased, or even talk about them.

The souls of Nanai infants do not behave in the same manner as an adult’s. For the Nanai, children under a year old are not yet people, but are birds. When an infant dies, its soul will turn into a bird and fly off. When an infant dies they are not buried. Instead they are wrapped in a paper made of birch bark and placed in a large tree somewhere in the forest. The soul of the child, or the bird, is then free to enter back into a woman. It is common practice in preparing a funeral rite of an infant to mark it with coal, such as drawing a bracelet around the wrist. If a child is later born to a woman that has similar markings to those drawn on a deceased child then it is believed to be the same soul reborn.

Today many Nanai are also Tibetan Buddhist. The Nanai language belongs to the Manchu-Tungusic family. According to the 2010 census there were 12,003 Nanai in Russia.

Explore our learning and certification programs that connect people with nature: www.wildcraftforest.com

Loved the film thank you